A statement from the Walkley Foundation

2 September, 2023

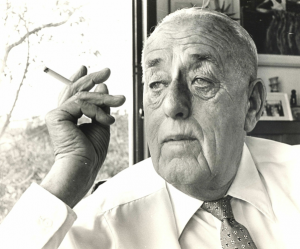

The Walkley Foundation has condemned and expressed deep regret for racist views expressed by the founder of its major awards Sir William Gaston Walkley in a newspaper column in 1961.

“His views do not reflect the values, views and ethics of the Walkley Foundation. We apologise for the deep hurt and offence these statements will have caused for journalists and the broader community,” the board of directors said in a statement today.

“As an ethical organisation, we must call out the mistakes of the past.”

By Helen O’Neill

News broke on Thursday June 28, 1956, that the Australian Journalists’ Association (AJA) had partnered with William Gaston Walkley, the Managing Director of Ampol Petroleum, to launch the country’s first national press awards.

The inaugural Walkley Awards prize pool would be £1,000 split across five categories – £500 for the first prize (best piece of newspaper reporting); £200 for the second prize (best feature story); then £100 each for best news or general interest picture, best story in an Australian magazine and best story in a provincial newspaper.

Judging would be organised by the AJA. Walkley would personally present the prizes, but beyond that would have nothing to do with the awards. So why was he sponsoring them?

“During my business activities I have come in close touch with many journalists in all parts of Australia and have always held them in high esteem,” Walkley told The Southern Cross News. “Never once has a confidence been breached … I have been reported accurately and fairly.

“For some time, I have considered expressing in some practical form my appreciation and admiration of newspapermen.”

Australia had nothing to compare to America’s Pulitzer Prizes, he continued. “So I decided to do something about it.”

Simple enough, it seemed, and a hell of a year to pick. In 1956, major stories erupted on almost every front, from international relations (Britain began nuclear weapons testing at Maralinga); sport (Melbourne played host to the Olympics); technology (TV channels flickered into life – first locally with TCN-9 in Sydney, then nationally on ABC TV); the weather (the Murray River suffered its worst recorded flood, triggering deluges across three states) and politics (NSW took the landmark step of legalising poker machines in registered clubs).

The nation’s most respected newspapermen must have considered themselves in with a good chance. Yet Wednesday December 19 brought the announcement that the top Walkley Award had been won by an unknown called Eva Sommer, a 22-year-old cadet reporter from the Sydney Sun.

Sir William Gaston Walkley (third from the left) congratulates Eva Sommer (centre) for winning the first Walkley Award.

Sommer, whose previous articles were largely soft news and gossip, had managed to secure an interview with a man who became known as “The Silent One”. This mysterious stowaway spent months imprisoned on the Italian ship Surriento as it shuttled between Europe and Australia, unable to set foot on land anywhere because he could not, or would not, reveal his name.

The cadet reporter was fluent in French and German, both of which the stowaway spoke. She interrogated his claim that he was an amnesiac, confirmed him to be a former prisoner of a Nazi concentration camp and fought to establish his right for refugee status.

Her scoop transfixed the nation. It resulted in the traveller being identified as 28-year-old Polish refugee Jakob Bresler and being allowed into Australia, and gave Sommer a moment of well-deserved fame. The Walkley archives hold a photograph of Sommer being towered over by the other (all male) 1956 prize winners. Walkley is resting his hand on her shoulder.

It should have marked the start of a brilliant career for Sommer, yet for reasons that remain unclear she receded from view.

But then the history of the Walkley Awards is full of surprises, not least how it all began – with the birth of William Gaston Walkley on Sunday November 1, 1896, in Otaki, a small coastal town between Wellington and Whanganui on New Zealand’s North Island.

Young Bill, the only son of London migrants Herbert and Jessie Walkley, displayed a no-nonsense approach to life early on. At 15 years old, realising he needed a bicycle for his first job as a telegraph messenger, he grew and sold potatoes to fund it. After World War I broke out, he joined the New Zealand Expeditionary Force and got as far as England, but did not see action before hostilities ended. Back home he qualified as an accountant and started his own practice.

According to Show Me A Mountain, Colin Simpson’s 1961 history of the first 25 years of Ampol, Walkley’s professional life was anything but dull. In 1926, he narrowly escaped a poisoning attempt by an embezzler whom he was about to expose (the embezzler was charged with attempted murder). Walkley then unmasked a fraud by a farmer who had been illegally rebranding his cattle for auction with a coded mark that let certain other bidders know whether the cows were good milkers. Suspecting foul play, the accountant borrowed clippers from a local barber to expose what was going on.

Walkley’s escapades brought him to the attention of William Arthur Callaghan, the president of the North Island Motor Union, the policy-making branch of the Automobile Association, or AA. In 1931 Callaghan hired Walkley as the Motor Union’s company secretary, and they co-founded the Associated Motorists Petrol Company in an attempt to counter the high petrol prices being set by overseas oil companies.

By 1935, Walkley had decided that Australia was where real money was to be made.

“I, therefore, sold my practice and other assets and moved to Sydney to form the company which we now know as Ampol,” he said in a 1960 speech.

“I took an office consisting of one room in Macquarie Place and had one typist at 30/- (shillings) per week and not a great deal of money. It is now 25 years since Ampol commenced marketing in Australia … our assets exceed £56 million and will be close to £60 million by the end of the current year.”

Walkley had convinced overseas petrol suppliers to allow Ampol to sell their fuel, but was determined to find out whether Australia could produce its own oil. By the late 1940s, Ampol had permits to explore vast tracts of Western Australia. When drilling began in the Exmouth Mouth in 1953, Walkley hired a DC-4 aeroplane to fly a press contingent there and show them what he was doing.

He would later hire three of the journos to key positions at Ampol, including Terry Southwell-Keely, a distinguished war correspondent and former deputy chief of staff of The Sydney Morning Herald.

On Friday December 4, 1953, the SMH news desk received a cable from Standard Oil of California announcing that Ampol had struck high-grade crude. Southwell-Keely phoned Walkley to congratulate him, only to hear Walkley say: “This is the first I’ve heard about it … I’ll phone [to check] and ring you back.”

Southwell-Keely joined Ampol as public relations manager not long afterwards, and as Ampol’s profits soared so, under his guiding hand, did Walkley’s nation-building initiatives. Ampol supported organisations as diverse as the Surf Life Saving Association, the University of Sydney’s Nuclear Research Foundation and Musica Viva. He also supported sports such as golf, soccer and indoor bowling, and introduced awards in a myriad of fields from farming to fishing.

Sir William Gaston Walkley

When Southwell-Keely suggested Ampol initiate national journalism awards, Walkley is said to have jumped at the chance. That he had the awards named after him suggests that he considered them particularly significant.

He certainly saw journalists as useful, in 1961 telling a Queensland business group keen to develop tourism that two Walkley Awards had been won by writers of the Townsville Bulletin.

“You have a fine group of press writers here and I feel you should enlist their aid in setting up the best public relations organisation in Australia,” Walkley advised. “You have talent in your midst.”

Walkley received the CBE in 1961, retired from Ampol in 1963 and was knighted in 1967. He presented the Walkley Awards every year until ill health stopped him, and died in Sydney on Monday April 12, 1976. He was 79.

In 2019, his family’s connection with the awards continued with a bequest to the Walkley Foundation of $1 million from June Andrews, Walkley’s sister-in-law, who had died two years earlier.

Much has changed since the Walkley Awards were launched, across journalism, the fossil fuel industry and Ampol, which was bought out by Caltex in 1997. In 2020, Caltex Australia was renamed Ampol Limited and a reassessment of the company’s history began.

This year, the company became a major sponsor of the Walkley Foundation, a step Matthew Halliday, Ampol’s CEO and managing director, describes as a logical progression in the rebranding process.

“It is about recognising the history of the founder of Ampol,” says Halliday, describing Walkley as a “highly entrepreneurial character, very much a people person … [who] built a company with a real purpose out of the ground, and managed to do it by developing a close relationship between country and company and community.”

In Halliday’s mind, the notion of “journalists and the media having a strong and effective voice on the future of the country” was fundamental to what drove Walkley and is equally important today as the world faces a transition from fossil fuels to green energy sources.

“[Fossil] fuel is going to disappear over the next couple of decades,” Halliday says. “The role that governments will need to play – and companies – in shaping what society is going to look like over the next 10, 20, 30 years, you need to have a very independent and capable media to … arbitrate that debate effectively.”